The art of Japanese seal carving, known as hanko or inkan, is a centuries-old tradition that continues to play a vital role in both personal and professional life across Japan. Unlike Western signatures, these intricately carved stamps serve as legally binding marks of identity, used for everything from banking transactions to official documents. The craftsmanship behind each seal reflects a blend of cultural heritage, artistic precision, and functional design, making it a fascinating subject for those interested in Japanese customs.

Historically, the use of seals in Japan dates back to the Yayoi period (300 BCE–300 CE), with influences from Chinese practices. However, it was during the Edo period (1603–1868) that hanko became widespread among the general populace. Initially reserved for nobility and officials, the democratization of seal carving mirrored societal shifts, eventually becoming a staple in everyday life. Today, every Japanese adult typically owns at least one registered seal (jitsuin), often stored in a protective case and treated with great care.

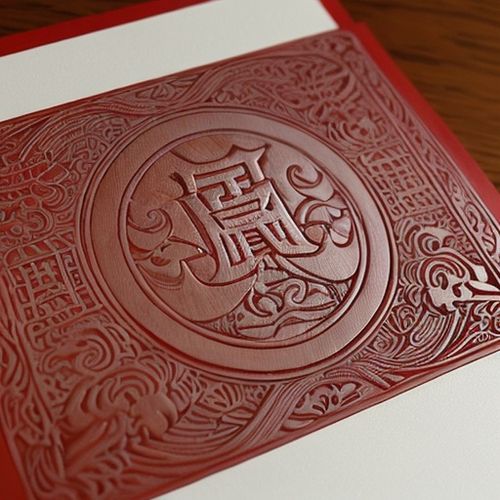

The process of creating a hanko is as meticulous as the tool itself is precise. Master carvers, or hanko-shi, train for years to perfect their technique. Materials range from affordable plastics and woods to luxurious ivory or ox horn, each selected for durability and aesthetic appeal. The carving itself is done using fine chisels, with the artisan’s steady hand dictating the seal’s unique character. The result is a mirror-image design, often featuring the owner’s name in kanji, though some opt for katakana or even romaji for international use.

What makes Japanese seals particularly distinctive is their classification into three main types: jitsuin (registered seals), ginkō-in (bank seals), and mitome-in (casual seals). The jitsuin, used for legal contracts and property deals, is the most formal and requires registration at local government offices. Its design must adhere to strict guidelines to prevent forgery. Ginkō-in, as the name suggests, is exclusively for financial transactions, while mitome-in handles everyday approvals like package deliveries. This hierarchy underscores the seal’s role in maintaining societal order.

Modern technology has introduced alternatives, such as digital signatures, yet the hanko persists as a cultural cornerstone. Recent debates about its necessity in paper-heavy bureaucracies have led to reforms, but the emotional attachment to these seals remains strong. For many Japanese, a hanko is more than a tool—it’s a symbol of trust, identity, and continuity in an ever-changing world. Whether crafted by a seasoned hanko-shi

By Laura Wilson/Apr 14, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 14, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 14, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 14, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 14, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 14, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 14, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 14, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 14, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 14, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 14, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 14, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 14, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 14, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 14, 2025