Across the vast and diverse continent of Asia, one common thread binds many of its sacred spaces: the act of removing one’s shoes before entering a temple. This simple yet profound gesture transcends national borders, religious denominations, and cultural differences. From the bustling streets of Bangkok to the serene mountaintops of Japan, the practice speaks volumes about respect, humility, and the spiritual significance of these hallowed grounds.

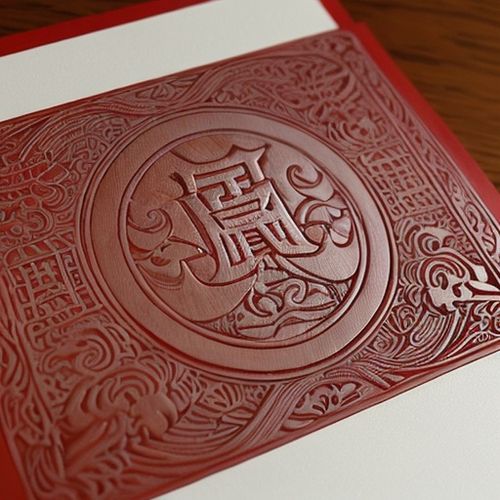

The tradition of removing footwear before entering temples is deeply rooted in Asian cultures. In countries like Thailand, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka, where Theravada Buddhism thrives, it is considered a mark of reverence. Temples are not merely buildings; they are embodiments of the divine, and the ground within is seen as pure. Shoes, which tread through the dirt and grime of the outside world, are viewed as contaminants. By leaving them at the door, visitors symbolically shed their worldly impurities before stepping into a space of worship.

In Japan, the practice extends beyond temples to include homes and even some traditional restaurants. The concept of “separation between inside and outside” is deeply ingrained in Japanese culture. The genkan, or entryway, serves as a transitional space where shoes are exchanged for slippers or bare feet. When visiting Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples, this custom takes on an added layer of spiritual meaning. The act of removing shoes is not just about cleanliness but also about leaving behind the chaos of the external world to enter a realm of tranquility and reflection.

India, with its myriad of religions and traditions, also observes this practice widely. In Hindu temples, the removal of shoes is a non-negotiable requirement. The sanctum sanctorum, where the deity resides, is considered the abode of the divine, and footwear is seen as a sign of disrespect. This belief is so deeply held that even in modern urban temples, where marble floors gleam under artificial lights, the rule remains unchanged. Sikh gurdwaras, too, enforce this practice, emphasizing equality—no one, regardless of status, is allowed to wear shoes inside, ensuring all are on equal footing before the divine.

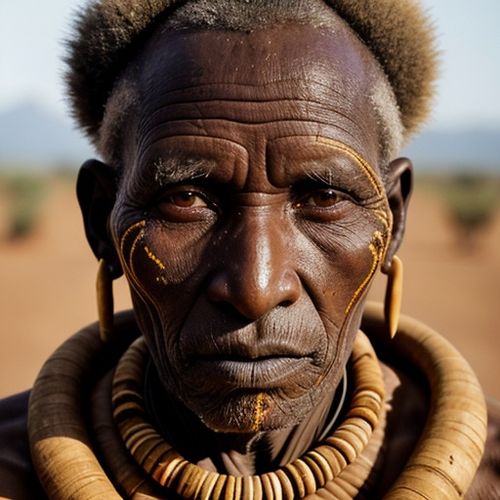

The reasoning behind this custom varies slightly from culture to culture but converges on themes of purity and respect. In many Asian belief systems, the feet are considered the lowest and least clean part of the body. To bring them, clad in shoes, into a sacred space is to dishonor the sanctity of that place. Conversely, walking barefoot signifies humility and a willingness to submit to a higher power. It is a physical manifestation of an inward attitude—one that acknowledges the sacredness of the space and the smallness of the self in the face of the divine.

For travelers unfamiliar with this tradition, the experience can be both enlightening and daunting. Stepping into a temple barefoot connects one to the earth in a way that is rare in modern life. The coolness of stone floors, the texture of woven mats, or the occasional unevenness of aged wood all serve as reminders of the tactile, immediate nature of spiritual practice. However, it also requires a degree of cultural sensitivity. Tourists are often reminded—sometimes through signs, sometimes through gentle admonishments—to comply with this practice. Ignoring it is not just a breach of etiquette but a profound faux pas that can offend local worshippers.

Beyond its spiritual implications, the no-shoes rule also has practical benefits. Temples, often centuries old, are preserved with great care. Shoes, with their hard soles and potential for carrying debris, can damage delicate floors or intricate carvings. In tropical climates, where many temples are located, the absence of shoes helps maintain cleanliness, preventing the tracking in of mud, dust, or worse. This practical aspect dovetails neatly with the spiritual, creating a holistic approach to temple maintenance and reverence.

Interestingly, the practice has also found its way into contemporary interpretations of sacred spaces. Modern Buddhist centers in the West, for instance, often adopt the no-shoes policy as a way to honor tradition and create a distinct atmosphere. Even outside religious contexts, the idea of removing shoes to denote a shift from the profane to the sacred resonates with many. It serves as a tangible ritual, a way to mark the transition from the hustle of daily life to a space of quiet contemplation.

Yet, like all traditions, this one is not without its challenges. In an increasingly globalized world, where tourism brings millions to Asia’s temples each year, enforcing the no-shoes rule requires constant vigilance. Some temples provide shoe racks or plastic bags for visitors to carry their footwear, while others rely on the honor system. There are occasional debates about hygiene, particularly in crowded urban temples where thousands of bare feet tread the same path daily. Nonetheless, the practice endures, a testament to its deep cultural and spiritual significance.

Ultimately, the act of removing one’s shoes before entering an Asian temple is more than a cultural quirk—it is a bridge between the mundane and the sacred. It invites participants, whether devotees or curious visitors, to engage with the space in a deliberate, respectful manner. In a world that often moves too fast, this small ritual forces a pause, a moment of consideration before crossing the threshold. And in that pause lies the heart of the practice: a recognition that some spaces demand more from us than others, not in grand gestures but in simple, humble acts of reverence.

By Laura Wilson/Apr 14, 2025

By Joshua Howard/Apr 14, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 14, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 14, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 14, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Apr 14, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 14, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 14, 2025

By Eric Ward/Apr 14, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 14, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 14, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 14, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 14, 2025

By Samuel Cooper/Apr 14, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 14, 2025